In an earlier blog, Finding Wendy, I recalled my first encounter with Stephen Downing. Stephen was just 17 years old in September 1973, when Wendy Sewell was murdered in Bakewell Cemetery where Stephen worked as a groundsman.

Stephen was the first person on the scene after Wendy’s attack, and as such was then treated as number one suspect by Derbyshire Police.

There are already numerous accounts of that day available for public consumption, so I’m not going to reinvent the wheel here. But in summary for those not familiar with the case, many eye-witness accounts discounting the possibility of Stephen as a suspect, were forthcoming, but ignored by police. Several timelines didn’t add up, reported sightings of other potential people of interest were covered up, and anyone trying to dig deeper into the case, or provide evidence to the contrary, was blocked at every turn. Evidence was destroyed or ‘lost’, and bringing things right up to date, key documents and records pertaining to the case, have been embargoed by the Home Office and Derbyshire Constabulary. In October of 2025, I made a formal Freedom of Information request to Derbyshire Constabulary, asking for a copy of Stephen’s original confession statement. My request was refused, for numerous reasons, and the upshot is that every time the case is reopened, the Home Office embargoes all related information for another 20 years. I was informed that the case had been reviewed as recently as 2020, which meant the embargo had been reset at that point. If you’re interested in seeing their full response, you can view it here.

One reason their refusal is unfathomable to me, is that a version of the statement already appears in Don Hale’s book ‘Murder in the Graveyard’, which tells the story of Don’s relentless journalistic work that was instrumental in Stephen’s release. I had originally considered using it as the subject of my research for this blog, but, as a keen checker of facts, I realised that the version in the book may very well have been subject to edits, and could not be guaranteed verbatim. But with this option now the only one open to me, I decided to go straight to the source, and contacted Don Hale directly, for his recollections. Don very kindly gave me two hours of his time on the phone, but sadly, couldn’t remember whether or not the published version of Stephen’s statement had in fact been edited.

I’m therefore left with little choice other than to use what’s available to me. So for the purposes of this blog, the version of Stephen’s confession statement that I use for analysis, is the one taken from Don’s book.

But don’t get me wrong, the points I present here are simplistic at best. Forensic Linguistics is a science that takes years to qualify in. My course at the University of Manchester barely scraped the surface. However, the features of Stephen’s statement that I do highlight, may form a strong enough foundation to motivate an expert to carry out a complex and scientific analysis, the likes of which, is at a level I won’t see for some years yet.

What is Forensic Linguistics?

In simple terms, Forensic Linguistics is the examination and analysis of written and spoken language, for use as evidence in criminal cases. The term was first coined in 1968 by Swedish Linguist Jan Svartvik, following his research into the Timothy Evans case from 1949. Police had forced Evans to make a statement about his involvement with the murder of his wife and baby at their home in Rillington Place in London: the scene of many crimes now known to be the work of serial killer John Christie. Svartvik used new techniques to break down the language used in the Evans Statements, concluding that the statements were likely to be false and that Evans had been coerced by police. He presented his findings in a document entitled, ‘The Evans Statements: A Case for Forensic Linguistics‘, which is acknowledged as the early foundation for what is now a recognised discipline, increasingly called upon in criminal cases. It’s important to note however, that by their very nature, the findings presented by Forensic Linguists can never be considered 100% conclusive, and are therefore always presented as the scenario ‘most likely to be true’.

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

Despite Stephen being 17 at the time of Wendy’s attack, he did in fact have learning difficulties, and presented the literacy abilities equivalent to an 11 year old. As a minor, Stephen should have been interviewed with an appropriate adult present, but this was not the case; he was interviewed alone. What’s more, police interviews were not recorded in 1973, so no impartial account of events exists. Don Hale describes the interview scenes in his book, and they don’t make for pleasant reading. During one of our regular coffees, Stephen recounted the events of that night, telling me that he was questioned for 9 hours, with no access to family, and was constantly hit and shaken awake by police. He was denied a lawyer and at no point was he advised that he was under arrest. Stephen was told if he came clean, he could go home, and in his naivety, that’s exactly what he did. So, being unable to write too well himself, Stephen’s statement was taken down by the officers.

Worryingly, they wrote it in pencil, and got him to to sign it in pen.

Vulnerable witnesses

False confessions come in two forms: those which are voluntary, and those which are forced through interrogation.

Many forensic and psychological studies have been carried out on ‘police-induced’ false confessions, and much information has been gathered on the tactics used, and those witnesses most susceptible. They are as follows:

- It will come as no surprise, that children and juveniles are the most vulnerable group. Within that group, those with compliant personalities or learning challenges are even more at risk. Stephen was 17, with a reading age of 11.

- Witnesses whose English language is weak. This includes non-native English speakers, and importantly, native speakers with communication issues, such as Stephen’s.

- Those who have endured lengthy interrogation. Stephen was held for 9 hours.

- Finally, those whose interviews are ‘guilt-presumptive’, i.e., when police are already convinced they ‘have their man’. Stephen was found at the scene, with the victim’s blood on his clothes. Police simply wanted a quick conclusion to the case, to avoid further mass panic in their small, close-knit community.

The Statement

This is Stephen’s confession, as presented in ‘Murder in the Graveyard’, by Don Hale:

I don’t know what made me do it. I saw this woman walking in the cemetery. I went into the chapel to get the pickaxe handle that I knew was there. I followed her, but I hadn’t talked to her and she hadn’t talked to me, but I think she knew I was there. I came right up to her near enough. I just hit her to knock her out.

She fell to the ground and she was on her side, and then she was face down. I rolled her over and started to undress her. I pulled her bra off first. I had to pull her jumper up and just got hold of it until it broke, and then I pulled her pants and her knickers off.

I started to play with her breasts and then her vagina. I put my middle finger up her vagina. I don’t know why I hit her, but it might have been to do with what I have just told you. But I knew I had to knock her out first before I did anything to her.

It was only a couple of minutes. I was playing with her and there was just a bit of blood at the back of her neck. So, I left her, went back to the chapel, got my pop bottle and went to the shop, and then went home to see my mother and asked her to get a bottle of pop for me because the shop was closed. I suppose I did that so that no one would find out I’d hit the woman.

I went to the cemetery about 15 minutes later and went back to see the woman. She was lying on the ground the same way I’d left her but she was covered in blood on her face and on her back. I bent down to see how she was and she was semi-conscious, just. She put her hands up to her face and just kept wiping her face with her hand. She had been doing that when I first knocked her down.

I went to the telephone kiosk to ring for the police and ambulance so they would think someone else had done it and I’d just found her. I hadn’t any money so I went to the lodge and asked Wilf Walker if he was on the telephone, but he said he wasn’t. So, I told him what I’d supposed to have found. He came to have a look and then he went to ask these other blokes in a white van outside the cemetery if they had seen her, but they said they hadn’t, so one of them went to phone for the police. I just stayed because there was no place to go.

(464 words)

Now, before we get into the linguistic technicalities, there are a few key points to note regarding the content. First of all, note how sketchy the detail is. There is nothing in that statement, exclusive to Stephen. Everyone at the scene was privy to the same information. He already knew that a pickaxe handle had been used as the murder weapon, because it had been left at the scene. He already knew that Wendy’s clothes were strewn around the cemetery, because that’s how she’d been found. But what he couldn’t have realised, was that the coroner’s examination, which had not yet been performed at this point, actually went on to reveal multiple blows to Wendy’s skull, not just the one blow described by Stephen. And whilst blood spatter had been found on Stephen’s clothes, this was only forensically compatible with his original claim that he had knelt beside Wendy to help, and that she had shaken her head, spraying blood onto his jeans. This blood spatter was NOT compatible with the blood that would have been present on someone who had carried out such a frenzied attack, as the one suffered by Wendy.

And So To The Linguistics

In order to carry out even a basic analysis of Stephen’s statement, I need a comparative corpus. In simple terms, a corpus is a collection of language used for reference purposes. Many are available, some are a corpus of general language, some are specialised. Google, for example, can be used by everyone, as a corpus of modern day language, but for this blog, I need something more specialised, to give me comparison texts from similar scenarios.

Because we suspect that Stephen’s statement is false, we need to compare its key features against another statement known to be false, and also against a statement we know to be true.

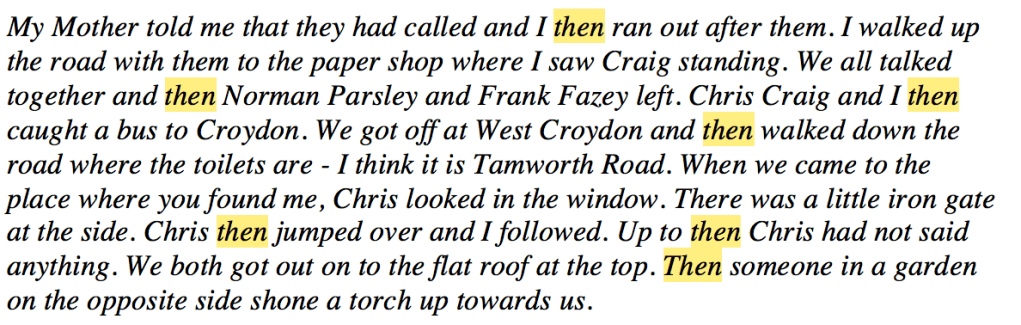

As the known true statement, I used the confession given by Peter Sutcliffe in 1981. We know his statement was genuine, not coerced, and full of detail that only a killer could have known. For the comparative false statements, I used two. Firstly, the Timothy Evans case previously mentioned. Evans made multiple statements to police, creating a small corpus which is 100% relevant to this analysis; and secondly, that of Derek Bentley, who was hanged at the age of 19, for the murder of a police officer in 1952. Bentley was posthumously pardoned in 1993 following the analysis of his confession statement by Forensic Linguist Malcolm Coulthard. His conviction was quashed in 1998 by the CCRC, and his name finally cleared, largely as a result of the linguistic evidence presented.

Derek Bentley: The Overuse of ‘Then’

One of the key takeaways from Coulthard’s analysis of Bentley’s statement, was that the word ‘then’ seemed to appear far more than you’d expect to find in every day speech.

There are of course different uses of the word ‘then’. As a conjunctive adverb, then is used to link two clauses of the same sentence, to show the sequence in which events happen, e.g, “I went to the shop, then I came home”.

It can also be used to denote consequence. i.e., the impact that one event has on another, e.g., “You don’t have coffee? I’ll have tea then”.

The comparisons in Coulthard’s research (and in mine) are all concentrated on the sequential form of then, when it’s used to show the order of events.

Coulthard compared this feature against a collection of ordinary witness statements, a collection of statements made by police, and also against the ‘Bank of English Corpus’, which at the time held over 100 million words and phrases (it now holds over 650 million). Here’s what he found:

In the language used by ordinary witnesses, ‘then’ appeared only once in every 930 words.

In the Bank of English corpus, it appears once in every 500 words.

By comparison, in the police statements, the word ‘then’ appeared once in every 78 words.

And Derek Bentley’s statement? Once in every 50.

This very simple test alone, suggests that the language in Bentley’s statement was more aligned with that commonly used by police rather than with that of the general British public.

To prove the point, even in the following short excerpt from Bentley’s statement, the word ‘then’ in its sequential form, appears no less than 7 times. The piece is 161 words long, so that’s 1 in every 23 words.

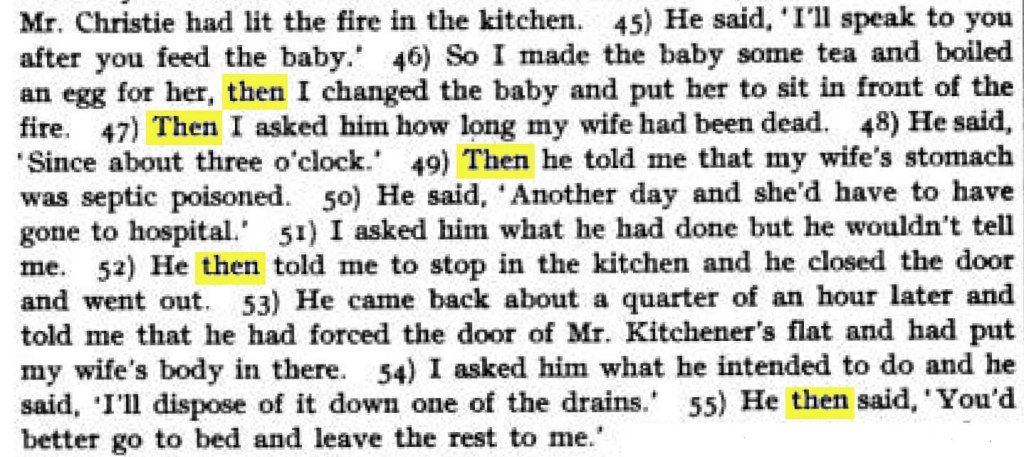

The Evans Comparison

Our second ‘known false’ statement comes from Timothy Evans. Evans made multiple, very lengthy statements, so here’s a random excerpt around the same length as Bentley’s:

In this 182-word sample, ‘then’ appears 5 times. That’s 1 in every 36 words.

The Sutcliffe Comparison

In what we know to be a true confession, Peter Sutcliffe voluntarily spewed out 10,910 words to police over the course of two days. In his entire statement there are only 32 instances of ‘then’ and two of those can be discounted due to context.

This is only 1 in every 363 words; and more clearly aligned with the Bank of English Corpus. It’s certainly a far cry from the 1 in 50, 1 in 23 and 1 in 36, shown in the examples of false statements.

Stephen’s Results

Stephen’s statement is 464 words long, containing 5 instances of the word ‘then’ in the relevant context. That’s 1 in every 92 words.

Stephen’s numbers sit well within the range found in the false statements, and police statements. When you couple that with the circumstances of his interrogation, his vulnerabilities, and the fact that police had covered up or ignored numerous eye-witness accounts, which cleared Stephen of any wrong-doing, it’s not hard to conclude there’s a strong likelihood that Stephen’s statement was forced.

Additional peculiarities in Stephen’s statement, support this conclusion.

Certain sentences are ‘clumsy’, and not what we might expect from a free-flowing narrative in which the speaker is using his or her own words.

For example, in the first paragraph, “I followed her, but I hadn’t talked to her and she hadn’t talked to me…” A more common form of words would be “We hadn’t talked to each other”.

It’s my personal view that the structure of Stephen’s sentence suggests he may have been answering questions, rather than talking freely. This makes more sense:

Q: Did you talk her, or did she talk to you?

A: I hadn’t talked to her and she hadn’t talked to me.

From the third paragraph, “I don’t know why I hit her, but it might have been to do with what I have just told you.” Again, sounds more like a possible answer to “Stephen, why did you hit her?”

Similarly, the very last line, “I just stayed because there was no place to go”, also feels more likely to be an answer to the question, “Why did you stay?”

These clues suggest that while Stephen was talking, the police were constantly throwing questions at him. This technique is discussed in ‘The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics‘, and is often used on vulnerable witnesses as a tactic to wear them down. In some cases, if the same questions or suggestions are repeated often enough by police, the witness will start to believe them to be true. Children and vulnerable adults are said to have ‘malleable memories’ that can be easily manipulated in this way, until they start to question their own innocence, and even convince themselves they are guilty.

Failed at Every Turn

Derek Bentley’s 1993 pardon was granted due to forensic linguistic evidence. So my question is, where was Stephen’s defence team in all of this? By 1993, Stephen had already served 19 years in prison, and a similar exercise carried out on his confession statement, may have massively strengthened an appeal. Why did this not happen?

Instead, Stephen wasted a further 8 years of his life behind bars, for a murder he did not commit. It was only thanks to Don Hale’s perseverance and campaigning, that Stephen was finally released on bail in February 2001. His conviction was quashed in January 2002.

Having spent significant time with Stephen over recent months, I can confirm that his life sentence is far from over. Police have maintained that Stephen remains their prime and only suspect in the murder of Wendy Sewell, and claim that all names put forward by Don Hale have been eliminated from their enquiries. One person in particular, who was seen by multiple witnesses running from the scene in a panicked and bloodied state, has escaped any further questioning. I’ve been told by someone with nothing to gain, that this individual was the adopted son of a Derbyshire police officer working on the case. He went on to become a prominent and esteemed university principal and was knighted in 2013. Quite a different hand to the one Stephen was dealt.

But if anyone should have the right to be judge and jury in this case, it’s the good people of Bakewell. Countless people who knew both Wendy and Stephen, went to the police with evidence at the time, only to be turned away. Countless people came forward when Don Hale asked for their help with his book, and countless people are fully aware of other young men who were involved but have never been so much as questioned.

Most importantly though, the town welcomed Stephen home, where they continue to treat him with the respect he deserves. And in a town as small as Bakewell, that could so easily have gone the other way.

If that’s not testament to a person’s character, I don’t know what is.

Feature photo is courtesy of the BBC, showing Stephen Downing (right), outside the High Court in January 2002 with Don Hale.